Komuso Shakuhachi Monks

Who were the Komuso shakuhachi monks?

Undoubtedly, the most iconic image next to the root end shakuhachi is that of the Komuso shakuhachi monks. I hope that after you read this that you’ll have come to better know these oft misunderstood Komuso.

Acknowledgements

For shakuhachi history my sources include the works of 國見昌史, Riley Lee, Kiku Day, Justin Senryu Williams, and Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson.

The Komoso

In mid 15th century literature we began to see mentions of shakuhachi playing ‘beggar monks’ called Komoso or ‘straw mat monks’ 薦僧/菰僧. Their name comes from the fact that they carried straw mats around with them to sleep on or to use as shelter from the elements. The Komoso would play shakuhachi for alms or donations, however, they were mostly laypersons of ‘commoner’ birth. In Japanese, the word for Buddhist alms begging is Takuhatsu (often pronounced “Takahatsu”).

Uchiyama Kosho Roshi (1912-1998) wrote, “The attitude of one on takuhatsu must be one of equanimity, whether no donation is received or a large one is received. In fact, the attitude of the mendicant on takuhatsu is one of giving an opportunity to people to materially support a life of one dedicated to zazen and the teaching of the Buddhadharma.”

As for their shakuhachi, the root end of the bamboo hadn’t come into use yet, as we saw previously with Ikkyu’s shakuhachi. Thus, the shakuhachi of the Komoso were crafted from ‘above root’ or ‘non-root’ bamboo. Shakuhachi were also shorter around 1.08 in length or ichi-shaku-hachi-bu (32.7cm/12.8in); 22cm shorter than the later and current standard of 1.8 or ichi-shaku-hachi-sun (54.5cm/21.5in).

The shakuhachi would also see other variations and evolutions before reaching the root end form we’re familiar with today (the root end did not come into use until nearly one thousand years after the arrival of the first shakuhachi in Japan, 8th c. to late 17th c.).

Komoso to Komuso

In the latter half of the 16th century an increasing number of Samurai found themselves ronin or ‘masterless’, mostly due to less wars. As a result, many more of these ronin Samurai began joining the ranks of the shakuhachi playing Komoso. It was also during this time that the Komoso became associated with the legendary Chinese Chan Buddhist sage Fuke Zenji (Japanese pronunciation). It’s speculated that this association was made in order to establish a Chan to Zen lineage in order to gain legitimacy for the group.

In the legends, Fuke Zenji would ring a small handbell for the purpose of teaching the Dharma. Whomever was creating the Komuso founding mythos seems to have been trying to make a connection between the bell of Fuke Zenji and the shakuhachi as another ‘sound device’ for spiritual Buddhist purposes. As such, in some texts the Komoso were additionally referred to as Fukeso or ‘Fuke monks’.

Eventually, the Samurai began calling themselves the Komuso 虚無僧. Over time, the ‘commoner class’ Komoso began to disappear from history as the ‘nobleman’ Samurai Komuso and the Fuke Shu sect grew. The Fuke Shu tried to make the act of playing shakuhachi for alms exclusive to the Komuso, and thus prohibited for non-Komuso ‘commoners’ to do so. Note that neither the Komoso nor the Komuso and their Fuke Shu Buddhist sect was ever officially recognized by the Japanese government nor any of the established Buddhist sects.

The Komuso of the Fuke Shu would go on to establish a network of temples, most notably the temples of Myoanji in Kyoto and Ichigetsuji in Edo, aka Tokyo. At some unknown point in time, the government prohibited the Komuso from owning Katana but they could carry a Wakizashi or ‘shortsword’, though this too was also eventually banned. They also began making shakuhachi from the root end of the bamboo, most likely during the 1700’s, and they extended the standard length by roughly 22cm; from 1.08 to 1.8 shaku.

The Kaido honsoku ‘Fuke Komoso’ Credo Version 1 海道本則

What follows is Torsten Olafsson’s translation of the Kaido honsoku ‘Fuke-Komoso’ Credo, Version 1 海道本則.

KAIDŌ HONSOKU

Document dated 1628, March 26th – Kan’ei 5, Mid-Spring, 21st day.

薦ハ何クカラ来テソフソ(ロ?)、

暗頭来也、暗キ國カラカ

明頭来也、明ナル國カラ歟、

Where from does the Komo come?

Fuke said,

‘The Dualistic Notion of “Darkness” appears … ‘

Does he come from the Realm of Obscurity?

Fuke said,

‘The Dualistic Notion of “Brightness” appears … ‘

Does he come from the Realm of Clarity?

コモノカムリタル笠ニ、不審カ候ヨ、

ソレ天蓋トモ申也、

Oh, how mysterious is the basket hat that the Komo is wearing on his head!

It is also called the ‘Tengai’.

肩ニカツキタル布ニフシンカ候ヨ、

神ノ前テノ御斗帳、

仏ノ前テノ鐘ノ緒、

虹蟠とも申なり、

Oh, how mysterious is the piece of cloth that he carries over his shoulder!

That is the ‘Dots-and-Cross’ patterned curtain in front of the Shintō Deity and the Bell String in front of the Buddha, and it is also called the ‘Rainbow Coil’.

セヲフタニ枚ノ御座ニフシンカ候ヨ、

サン候、地水火風空ノ義ナリ、

下一面目ハ三無不可得ノシメカクシノギナリ、

Oh, how mysterious is the double-leaf, fine straw mat that he carries on his back!

It represents the Tripartite Climatic Periods and the Five Elements: Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Space.

The first layer signifies the Total Concealment of the Ungraspability of the Three Existences: Past, Present, and Future.

中ニ入テセヲフタ袋ハフシンカ候、

ソレ天地ヲ沙汰シタ乾坤トモ申也、

How mysterious is the case that he carries on his back, inside the rolled up straw mat!

It is also called the ‘Kenkon’ which proclaims the Interrelatedness of Heaven and Earth.

上ニ着タル網ニ不審カ候ヨ、

海道ヲ囘センンカタメノ定袋トモ申ナリ、

Oh, how mysterious is the net that he has wrapped around the things!

It is called the ‘Prescribed Bag’ for accomplishing an exhaustive roundtrip through all the provinces.

結タル縄ニフシンカ候ヨ、

有無ノニ字トモ申ナリ、

Oh, how mysterious is the rope with which everything is tied together!

It is also called the ‘Two Concepts of Being and Non-Being’.

前ニ入レタル袋ニ不審カ候ヨ

五體ヲ表スルナリ、

夫六腹トモ申ナリ、

中ニ入タハ有雜無雜、

色ハ青黄赤白黒也、

Oh, how mysterious is the purse that he carries placed on his chest!

It expresses the Totality of the Human Body. It is also called the Six Internal Organs.

It contains miscellaneous things, their colors being bluish-green, yellow, red, white, and black.

薦ノ持タル竹ニフシンカ候ヨ、

尺八者コモノ重寶ヲ以テ、

四節四穴ト表スルナリ、

裏一穴ハ一心菩提明ト表スルナリ、

内ノ暗ハ閻魔法界ノ家ナリ、

三ノ節ハ三身一體、

本ノ切口ハ金剛界、

上ノ圓キ歌口ハ心月明ノマナヒナ、

合テ七百餘尊ナリ、

Oh, how mysterious is the bamboo flute that the Komo carries!

The shakuhachi is the principal treasure of the Komo and it represents the Four Seasons, likened to the four finger holes in the front.

The single finger hole on the back expresses the Clarity of the Enlightened, Adual Mind.

As for the darkness of its interior, that represents the Realm of Jurisdiction of the King of Hell, Judge of the Dead.

The three nodes represent the Oneness of the Three Bodies, the lower opening the Womb World, the upper opening the Diamond World, and the crescent-shaped mouthpiece above teaches the Clarity of Absolute Reality.

The shakuhachi is precious beyond limit.

神ノ前ニテ吹時ハ、

五衰三熱ノ苦ヲ除カンカ爲ナリ、

佛ノ前ニテ吹時ハ、

無明煩悩ノ眠ヲ覺サンカタメナリ、

智者ニ向テ吹時ハ、

平等専一切ノ息ヲ長メ、

無明凡人ヲ拂テ吹ベシ、

ソレ平人ニ向テ吹時ハ、

五相十相及盡囘向ト云也。

When the Komo plays in front of a Shintō Deity, it is to end the Suffering from the Five Types of Decay and the Three Fevers.

When the Komo plays in front of an image of the Buddha, it is to awaken from the Drowsiness of Earthly Desires Originating in Illusion.

When the Komo plays for educated persons, he should prolong his breathing in constant concentration and blow so as to drive away the Mediocre Body Originating in Illusion.

When he plays the shakuhachi for ordinary, uneducated persons, it is to explain all the Schools of Buddhism as well as performing all of the Buddhist Ceremonies.

コモト云フソノ水上ヲタスヌルニ

古モナク、 今モナシ、

亦云、 三界ハ無法、

見モノノママニ、

柳ハ緑、花ハ紅トモ申ナリ、

コモト云ソノ水上ノナカリセハ、

世ニヲチ人ノ家ハナキモノ、

サテ亦長門ニテ赤間カ關、

洛陽ニテ相坂ノ關、

奥州ニテ白河二所ノ關、

三關今役ナクシラ、

天地同根、萬物一體

天地豊繞ノコモニ、

關モ役モナシ、

If you inquire about the Komo’s place of origin, the answer is:

‘Neither in the Past nor in the Present!’

Or, to put it in the words of Banzan:

‘The Three-fold World is Immaterial!’

Any attempt at answering the question would be just as meaningless as saying ‘the willow is verdurous, the flower is crimson’!

Instead of a place of origin, the Komo are scattered in the world without such a place to call home.

And now being deprived of employment anywhere, be it at any of the three barriers of Akama-ga-seki in the Nagato Province, Ōsaka-no-seki at the [old] capital [Kyōto], or the two checking stations of Shirakawa in Ōshū, the Komo who abundantly wander the world, to whom Heaven and Earth have the Same Root and All Creation is One Body, have neither confinements nor attachments.

薦ノハイタル草鞋ニ不審申候ヨ、 盤石ヲ蹈定メンカ爲ノワラジナリ

Oh, humbly speaking, how mysterious are the straw sandals that the Komo is wearing!

They represent the proper footwear for the steadfast treading his way [on giant rocks] in the footprints of Banzan and Sekitō.

歌ニ云、

尺八ノ、聲ノ内ナル、隱レカヲ、

タスネテ見ハ、元ノ竹カナ、

切レコモハ見事ノ竹持テソフ(ロ?)、

It is said in a poem that,

‘When you search, and find in shakuhachi sound your refuge,

is that not indeed the essence of bamboo?’

The competent Komo possesses a magnificent piece of bamboo.

五尺ノ境界スゴサンガタメ、

薦ハ目ヲアマタ持テ、

ナゼニ獨ネヲスルゾ、

面ハ四目也、

So he may pass through the Five-fold Environments of Karma,

the Komo is observing many precepts

– and therefore he sleeps alone.

The surface has four eyes [or, stitches? – or, the face has four eyes?].

前ハ人ノ目ナレハ、

終りニ我トネル故ニ、

尺八聴聞ノ方ハ、

一息截斷ノ心ヲナシ、

無明凡人ヲネムリヲ拂テ

聴聞ヲ致スベシ、

Because the Komo practices celibacy till the end, he shall create a mind of relief and disconnection in those who listen to his shakuhachi sermons and sweep away the Drowsiness of Illusion and Mediocrity and bring about Realization.

歌ニ云、

尺八ノ、聲ノ内ナル、隱レカハ、

宮城野ニ吹く、春(ノ)風カナ、

Another poem has it that,

‘Choosing as one’s hermitage the voice of the shakuhachi

is that not the Spring breeze blowing at Miyagi-no?’

コモノ棒ニフシンカソロソ、

ギギスレハ白雲萬里、

How mysterious, indeed, is the Komo’s staff!

If you are doubtful, Setchō said,

‘White Clouds Everywhere!’

コモノ指タル刀ニフシンカソロソ、

屏風カ蒲團カ、

普化ハ七腰サシタト申、

How mysterious, indeed, is the sword that the Komo is carrying!

Even at Banzan’s deathbed Fuke made a somersault over the screen and mattress, it is being told!

薦僧開山普化和尚末派十六派アリ、

The Komosō founder Priest Fuke’s sect has 16 branches:

一 ワカサリ門派、

The Wakazari Branch Sect.

一 筑紫ニイヌヤロウ門派、

The Inu-yarō Branch Sect in Tsukushi.

一 北國ノキハ門派、

The Hokkoku Noki-ha Branch Sect.

一 中國ニノキハ門派、

The Noki-ha Branch Sect in Chūgoku.

一 伊勢ニサカハヤシ門派、

The Sakabayashi Branch Sect in Ise.

一 五畿内ヤワタノキハ門派、

The Gokinai Yawata Noki-ha Branch Sect.

一 武蔵カカリ門派、

The Kagari Branch Sect in Musashi.

一 美濃ニ若衆門派、

The Wakashū Branch Sect in Minō.

一 上州ニサラハ門派、

The Sara-ha Branch Sect in Jōshū.

一 中武蔵ニヨリタケ門派、

The Yoritake Branch Sect in C. Musashi.

一 下總ニキンゼン門派、

The Kinzen Branch Sect in Shimōsa.

一 下野ニコキクハ門派、

The Kogiku-ha Branch Sect in Shimotsuke.

一 奥州ニタンシヤクヨロコヒ門派、

The Tanjaku Yorokobi Branch Sect in Ōshū.

一 常陸ニウメジ門派、

The Umeji Branch Sect in Hitachi.

一 奥州ニタンシヤク派ヨ、

The Additional Tanjaku Branch in Ōshū.

一 北國ニカンタキノハ門派、

The Kandan-ki no ha Branch Sect in Hokkoku.

リワカル派アリ、

These are the rustic and humble branches.

暮露

Boro — ‘He/they who live(s) like the dew’.

寛永五仲春念一日

Kan’ei 5, Mid-Spring, 21st day.

The Possible Meaning of Komuso 虚無僧 – A deeper dive

To try and understand what 虚無僧 Komuso means, we’ll take a fascinating look into Chinese Chan Buddhism which becomes none other than Zen Buddhism in Japan. David Hinton in his book, “China Root: Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen”, writes, Chapter II [text in brackets mine]:

…original-nature is also known in Ch’an parlance as empty-mind (空心) [Kushin in Japanese. 空 refers to Śūnyatā: Sanskrit: शून्यता; Pali: suññatā.]

…空 [ku] itself also means quite simply “sky”

…Hence, empty-mind [空心 kushin] as “sky-mind.”

…空心 [kushin] is therefore quite literally the “original-nature” of consciousness.

…sky appears again in a synonym for 空 [ku] in the Taoist/Ch’an syllabary: 虚 [the same ko in Komuso 虚無僧.]

…[Huangbo Xiyun 黄檗希運, died 850] uses both of the terms for “empty/sky” when he describes mind as, “radiant purity like the emptiness of empty sky (空虚) [Kuko].” [空虚 Kuko reversed is none other than the title of the revered Honkyoku shakuhachi piece 虚空 Koku.]

…空 [ku] is synonymous in the Ch’an literature with 無 [mu] (absence) [the same mu 無 in Komuso 虚無僧]. Indeed, there is a common variation of 空心 [kushin] (“empty-mind”): 無心 [mushin](“no/absence-mind”), where 無 [mu] replaces 空 [ku] as a virtual synonym.

David Hinton in their book, “China Root: Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen”, Chapter II [text in brackets mine]

Therefore, the first two Kanji for Komuso 虚無 are virtually synonymous and of primary importance in Chan Buddhism. We also seem to see this expressed in the titles of Honkyoku pieces, such as the aforementioned 虚空 Koku and the piece 虚鈴 Kyorei or, ‘Empty/sky-mind Bell’. Lastly, 僧 or So simply means monk(s).

Komuso Spirituality

Honkyoku 本曲, the most venerated pieces of shakuhachi music, were primarily composed by anonymous Komuso monks and are considered to be spiritual, often inspired by Buddhism, Shinto, and/or Shugendo. The ‘genre’ is thought to have originated from the Southern island of Kyushu, Japan.

The word Honkyoku can refer to a single piece or to the genre as a whole. The Kanji for Hon 本 can mean ‘main/original/true/real’, while Kyoku 曲 can be taken as, ‘piece/composition/music’. Distinct regional styles developed across Edo period Japan, and while many Honkyoku are thought to have been lost, the surviving pieces comprise the largest body of solo wind instrument music in the entire world.

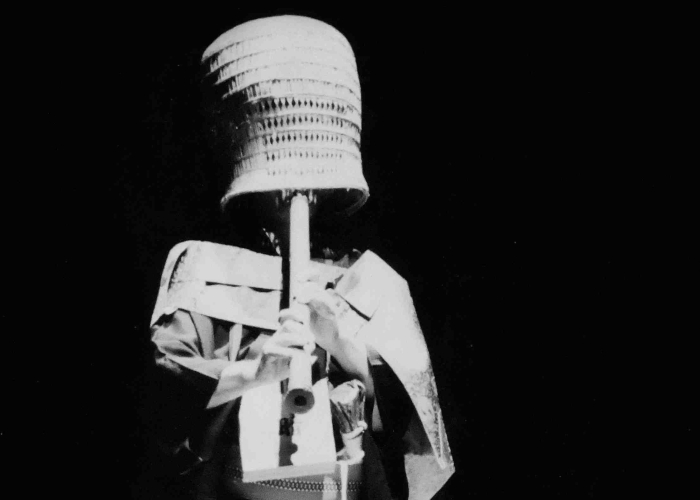

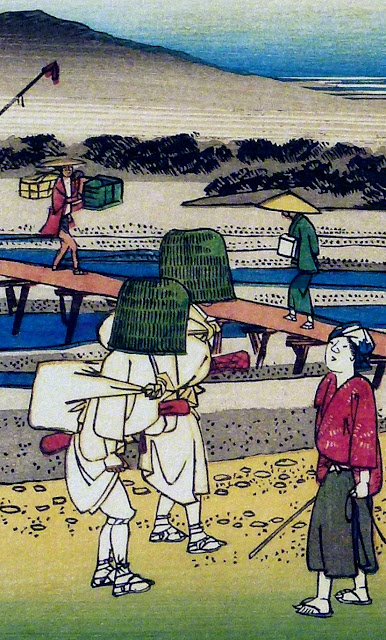

The Tengai Basket Hat and Other Komuso Vestments

The Tengai 天蓋 or ‘heaven cover’ hat is perhaps the most iconic Komuso item next to the shakuhachi. Like the shakuhachi, it saw an evolution, from generic straw hat to the iconic ‘beehive’ like shape which fully incases the head. It’s been said that its final form was a tool to aid in the suppression of the ego, as well as a means to help people to listen to the shakuhachi, rather than being concerned with the identity or emotions of the Komuso.

It’s also been speculated that it provided a disguise and/or a way to hide exactly how the shakuhachi was being played. The Tengai hat is typically woven from either grass reed, rattan, or even bamboo. It also has a unique headband ‘suspension system’ which is secured with string which allows the hat to move with the motions of the player.

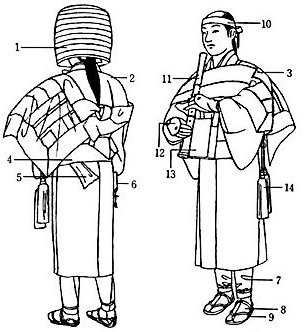

(Note that the ‘shortsword’ or Wakizashi is not included in this most likely modern diagram)

1. Tengai (天蓋) – basket hat; ten ‘sky/heaven’; gai ‘cover’

2. Kimono (紋付) – usually montsuki ‘five crest’

3. O’kuwara (大掛絡) – like Zen Rakusu except larger and worn over the shoulder

4. Obi or Kaku-obi (帯) – a stiff cotton belt

5. 2nd shakuhachi (usually fake these days)

6. Netsuke (根付) – place to store small items

7. Kyahan (脚半) – shin covers

8. Tabi (足袋) – split toe socks

9. Waraji (草鞋) – straw sandals

10. Hachimaki (鉢巻) – head band

11. Shakuhachi (尺八) – 1.8 ‘D/Db’ ichi-shaku-hachi-sun

12. Teko (手甲) – hand and forearm covers

13. Gebako (偈箱) – ‘alms box’ which could also hold the Kai in or ‘official documents’

14. Fusa (房) – tassel

Initiation of a Komuso

To become a Komuso of the Fuke Shu during the Edo period, one had to produce their papers of Samurai lineage, pay an entrance fee, and take oaths. The new Komuso would be given the San gu or ‘three tools’ and the San in or ‘three seals’. The ‘three tools’ were the shakuhachi, the Tengai, and the O’kuwara ‘shawl’ (Rakusu/kesa). The O’kuwara shawl is much like the Zen Buddhist Rakusu, however, the Komuso O’kuwara is larger and worn over the shoulder, instead of in the regular position in front of the body.

The San in were the Honsoku ‘Komuso license’ to beg, the Kai in or ‘personal identification papers’, and the Tsu in document which allowed them to cross borders. They were also given a Gebako which is a lacquered wooden alms box or cloth bag worn about the neck in which were stored the official papers. Some Komuso also received their alms in the Gebako box.

Activities of the Komuso

The chief activity of a shakuhachi playing Komuso would have been playing Honkyoku. Generally, a Komuso would beg for alms by playing a Honkyoku outside of a home, place of business, or in town. However, some Komuso were known to have practiced near extortion in order to receive alms by intimidating people, loitering, and causing ‘noise’. Additionally, some Komuso would play shakuhachi for auspicious events, such as funerals, and received alms for their services.

Perhaps most notably, Komuso could wander far and wide across Japan. For instance, it’s well known that Komuso traveled to other Fuke Shu temples where different regional Honkyoku styles had developed. In turn, this allowed for some ‘cross-pollination’ of these regional Honkyoku styles. For example, the famous Komuso Kurosawa Kinko I (1710-1771) collected various regional Honkyoku across Edo period Japan. His collection was posthumously codified into the Kinko Ryu school, which survives to the present day.

Shakuhachi as a weapon

We’ll never know to what extent or how often the shakuhachi was used as a weapon during the Edo period and earlier. However, what we should call into question are those who still perpetuate fantasies of bloodshed, especially without condemning violence, all in order to tantalize at the expense of the greater artistic and spiritual legacy of the Komuso monks and their direct descendants.

Teaching of Laypersons and the Evolution to Modern-day Instruction

The Fuke Shu attempted to keep the shakuhachi exclusive to the Komuso, however, many laypersons or ‘non-Komuso’ continued to play the shakuhachi. Over time, these ‘non-Komuso’ lay shakuhachi players became a part of Sankyoku secular ensemble music with Koto and the Shamisen. Near the end of the Edo period, the Fuke Shu actually began to allow Komuso to teach shakuhachi to laypersons for a fee. These students could also earn shakuhachi playing licenses and professional titles.

The Banning of the Komuso – The Meiji Restoration and the Dissolution of the Fuke Shu

It’s estimated by some that there were more than one hundred Komuso shakuhachi temples across Edo period Japan. However, the Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1889) abolished the practice of the Komuso which resulted in the closing, converting, or the destruction of the Komuso temples. Next, the new Meiji government decided to ban shakuhachi playing altogether, however, the Kinko Ryu Grandmasters Araki Kodo II (Chikuo I) and Yoshida It’tcho successfully petitioned the new government to allow secular shakuhachi music to continue.

Despite these challenges, the traditions of the Komuso persisted into the modern era. Today there are those who carry on the practices of the Komuso primarily via the preservation of the Honkyoku. In conclusion, the history of the Komuso is a testament to the enduring power of spiritual and artistic practices in the face of adversities. Despite persecution and many other hardships, the Komuso remained committed to their shakuhachi practice, inspiring generations of players.