Honkyoku: The Most Revered Shakuhachi Pieces

To begin learning, see my Shakuhachi Note Charts, and then, Your First Honkyoku Kyorei.

Honkyoku (本曲) survive as the most revered pieces of shakuhachi music. These profound compositions were primarily written by anonymous Komuso (虚無僧) which were the shakuhachi playing monks of the Fuke sect. For many, Honkyoku are considered deeply meditative and spiritual in nature. Both the compositions themselves and the diverse methods of playing them were influenced by Buddhism, Japan’s indigenous religion Shinto (神道), and various ascetic traditions such as Shugyo (修行).

This genre is believed to have originated on the southern island of Kyushu. Over time, distinct regional styles blossomed across Edo period Japan. While many pieces are thought to have been tragically lost during the tumultuous upheaval of the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), the surviving works collectively form the largest body of solo flute music in the entire world.

Behind the Name: Honkyoku

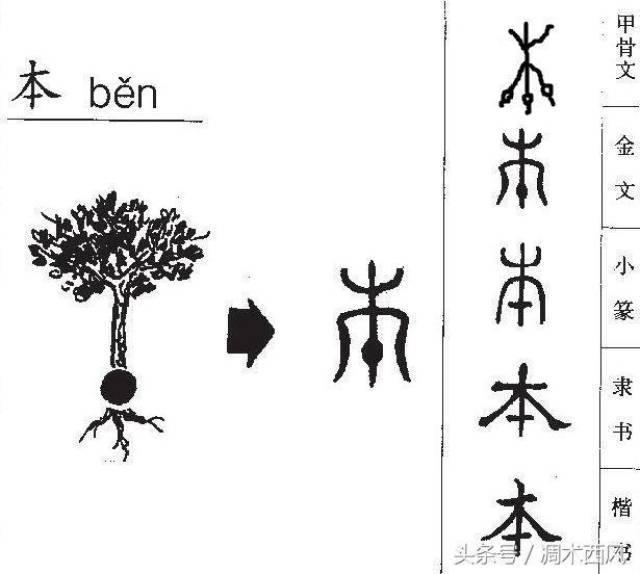

The word Honkyoku can refer both to a single composition and to the entire genre. The Kanji for Hon (本) beautifully depicts a tree with branches spreading above and roots reaching below, symbolizing foundation and essence. Kyoku (曲) translates simply to ‘piece’, ‘composition’, or ‘music’. Together they mean something like “original music” or “root composition”. The term may have been coined much later in the Edo period when the need to differentiate between them and secular shakuhachi music arose.

What Makes Honkyoku Unique?

Honkyoku pieces are truly unique in several profound ways:

- Solo and Spatial: They are predominantly solo compositions punctuated by deliberate pauses of silence between phrases. This allows the listener to notice the space after the sound.

- Unbound by Strict Rhythm: The majority of Honkyoku do not adhere to a strictly set rhythm or rigid melodic structures. While their composers were broadly influenced by Wagaku (和楽) or ‘Japanese music’, which in turn drew from Chinese and Korean traditions, the scales or modes used in Honkyoku, often called the ‘Koto scale’, are apparently endemic to Japan.

- Nuance Beyond Notation: These pieces are incredibly nuanced which makes transcribing them into Staff notation virtually impossible. Even traditional shakuhachi Katakana notation systems do not fully convey many of their subtle complexities. It’s akin to trying to infer or convey the accent of a regional dialect solely through written text alone. For this reason, the transmission of Honkyoku must occur between the teacher and their students.