Shakuhachi History

Acknowledgements

For shakuhachi history my sources include the works of 國見昌史, Riley Lee, Kiku Day, Justin Senryu Williams, and Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson.

Shakuhachi history – From China to Japan

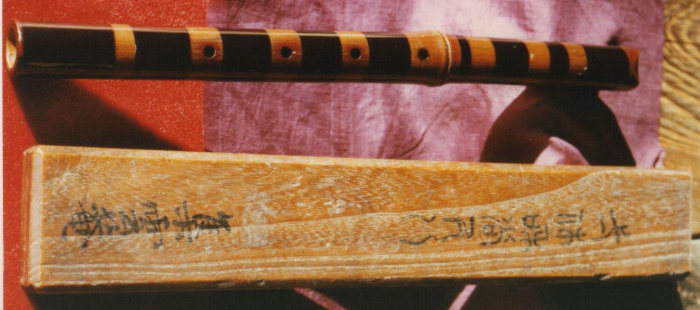

The ancestral flutes which the shakuhachi evolved from were first imported to Japan from China during the Nara period (710-794 AC). These flutes were a part of court music or Gagaku 雅楽, as it’s translated into Japanese. They were made from bamboo poles, jade, various stones, and ivory. Shakuhachi were also shorter around 1.08 in length or ichi-shaku-hachi-bu (32.7cm/12.8in; 22cm shorter than the later and current standard of 1.8 or ichi-shaku-hachi-sun or 54.5cm/21.5in).

The shakuhachi would also see other variations and evolutions before reaching the root end form we’re familiar with today. For example, the root end did not come into use until nearly one thousand years after the arrival of the first ancestral Chinese flutes in Japan (8th c. to late 17th c.).

Zen Buddhist Ikkyu Sojun

Ikkyu Sojun 一休宗純 (1394–1481) perhaps needs little introduction as he is one of history’s most well known Zen Buddhist figures. Ikkyu particularly loved playing shakuhachi and composed poems about it. In Volume 1 of the Shorin Mukuteki, a passage from Toyo Eicho recounts how he witnessed Ikkyu Sojun playing the shakuhachi in the Zen temple Daitoku-ji when he entered the Abbot’s Quarters to become its rebuilder and restorer (Kyoto, 1474). The following poems were sourced from the website of shakuhachi researcher Torsten Olafsson.

不寒臘後

看一休和尚

入牌祖堂正宗滅却。

狂雲吹起寶山巓。“In the not cold Winter, after the offering ceremony held on the third Day of the Dog after the Winter solstice [12th month, 1474], I saw Abbot Ikkyu as he entered beneath the sign board of the Founder’s Hall [of Daitoku Temple in Kyoto] after its destruction [in the Onin War, 1467-1477]. Kyoun [Ikkyu’s literary name] blew forth [on the shakuhachi the tune] Hosanten, Summit of the Treasure Mountain.”

Trsl. by Torsten Olafsson

On that day Ikkyu also recited the following poem attributed to Zhenzhou Puhua or Fuke Zenji titled Myoan 明暗 (more on Fuke and the Fuke Shu further down below).

明暗 Myoan, by Fuke Zenji

普化和尚

Poem in the ‘Kyoun-shu’. Trsl. by James H. Sanford, 1981

議論明頭又暗頭

老禅作略*使人愁

古往今耒風顛漢

宗門年代一風流

The monk P’u-K’o.

Arguing first at the Bright Head, then the Dark,

That Zen-fellow’s tricks fooled them all.

Now, blowing up again, the same old madman,

A sensual youth, howling at the door.

More poems attributed to Ikkyu Shojun which mention the shakuhachi

なかなかに

われに如かざる

人よりも

只尺八の

声ぞ友なるVery much so it is for me

Ikkyu Sojun

that even compared to the very best person

only the voice of the shakuhachi is really a friend.

尺八は

ひとよばかりと

思いしに

いくよか老いの

友となりぬるIn just one evening

Trsl. by Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson, 2010. Source: Nakatsuka, 1979, p. 66.

the shakuhachi made me realize

that for numerous nights to come

it has become like an old friend.

The Rural Monk in Uji

尺八

因憶宇治庵主曽

餒膓無酒冷於氷

明皇天上羽衣曲

偶落人間慰野僧Shakuhachi

Ikkyu Sojun, 1394-1481. Poem in the ‘Kyoun-shu’. Trsl. by James H. Sanford, 1981.

Even now I remember the recluse of Uji.

Empty belly, no wine, colder than ice.

Yet, that song of the angel’s shining cloak.

Lost among refugees, the rural priest takes comfort.

Komoso to Komuso – Commoner to Samurai

The shakuhachi was replaced in the Gagaku ensemble and later resurfaced in the hands of commoners, particularly the Komoso or ‘straw mat monks’ 薦僧/菰僧 who would play shakuhachi form alms. From the mid to late 16th century, many Samurai found themselves ronin or ‘masterless’, i.e., without a livelihood. As a result, an increasing number of them were joining the ranks of the Komoso shakuhachi beggar monks.

The Samurai went on to create their own exclusive order and began calling themselves the Komuso or ’empty/clear-mind monks’ (虚無僧). It’s generally believed that the Samurai Komuso eventually began using the root end of the bamboo for shakuhachi and they extended the standard length by roughly 22cm; from 1.08 to 1.8 shaku. While this form of the shakuhachi is notoriously compared to a cudgel, we’ll never know to what extent or how often the shakuhachi was used as a weapon during the Edo period.

An unofficial Zen Buddhist sect was formed by or for the Komuso called the Fuke Shu. The Tokugawa Shogun government allowed the Fuke Shu to establish themselves, though no formal recognition as a legitimate sect of Buddhism was ever granted. The Komuso developed a number of refined styles of Honkyoku which are considered to be spiritual or meditative pieces of shakuhachi music. (You can read more about the Komoso and Komuso here.)

The Meiji Restoration

The Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) was revolution that restored imperial rule to Japan under Emperor Meiji. One of the goals of the Meiji Restoration was to purge Japan of the foreign influence of Buddhism in favor of a nationalized version of Shinto. One of the early slogans of the Meiji Restoration was, ‘Sweep aside the Buddha: Smash Buddhism’.

As a result, during the Meiji Restoration the Fuke shu of the Komuso was dissolved, due to both its Buddhist associations and Samurai origins. This included the playing of Honkyoku which was also officially banned. Despite this, secular folk and ensemble shakuhachi playing with Koto and Shamisen continued to grow in popularity.

However, the Meiji Empire soon tried to ban the shakuhachi altogether. The Kinko Ryu Grandmasters Araki Kodo II and Yoshida It’tcho succeeded in petitioning the Empire to allow the shakuhachi in secular settings. Eventually, nonsecular shakuhachi activities were allowed to resume, however, the Fuke shu was never restored.

Shakuhachi in the 20th c. to now

Through the 20th century, the shakuhachi, like the rest of Japan, experienced relatively sweeping changes, both with its construction and the music which was played on it. For instance, an increasing number of shakuhachi practitioners were drawn to the Tozan Ryu with its focus on playing contemporary music genres on shakuhachi and learning to read Staff musical notation, in addition to Katakana based shakuhachi notation. To this day, in Japan the Tozan Ryu and non-traditional shakuhachi music dominate, however, all traditional arts are on an ever steeper decline in the country.

It was also in the 20th century that we saw a growing export of the shakuhachi to the rest of the world, both from Japanese and non-Japanese people. Most non-Japanese shakuhachi enthusiasts were drawn to the traditional forms of shakuhachi music, but especially the Honkyoku. Indeed, some estimate that within the early 21st century there will easily be more shakuhachi practitioners outside of Japan than within it. This is especially likely with the growing popularity of shakuhachi in other East Asian countries like China.

Additionally, as a direct result of Japan’s extensive ‘export culture’ via manga, anime, and video games, in the 21st century we’re seeing an increase in interest for the shakuhachi outside of Japan. For example, in 2020 the American developed game Ghost of Tsushima was the first to feature the shakuhachi as a playable accessory that gamers could use, thus introducing the instrument to thousands of people around the world.

Perhaps this will also ‘come back home’ and result in a resurgence of interest in the shakuhachi with Japanese people living in Japan. For now, there continues to be an ever diminishing interest in the shakuhachi within Japan along with all other traditional Japanese arts. For an idea of the situation all Japanese traditional art forms face, to varying degrees, see the video below by YouTuber Shogo san who also plays shakuhachi.